CLSA

Xi Jinping’s ambitious strategic initiative – an adaptation of the historical Silk Road – could sow the seeds for a new geopolitical era

Thirty years of unprecedented growth

In just 30 years, China has developed from a poor inward-looking agricultural country to a global manufacturing powerhouse. Its model of investing and producing at home and exporting to developed markets has elevated it to the world’s second-largest economy after the USA.

Now faced with a slowing economy at home, China’s leadership is looking for new channels to sustain its appetite for growth at a time when developing neighbours are experiencing rapidly rising demand.

A new economic paradigm emerges

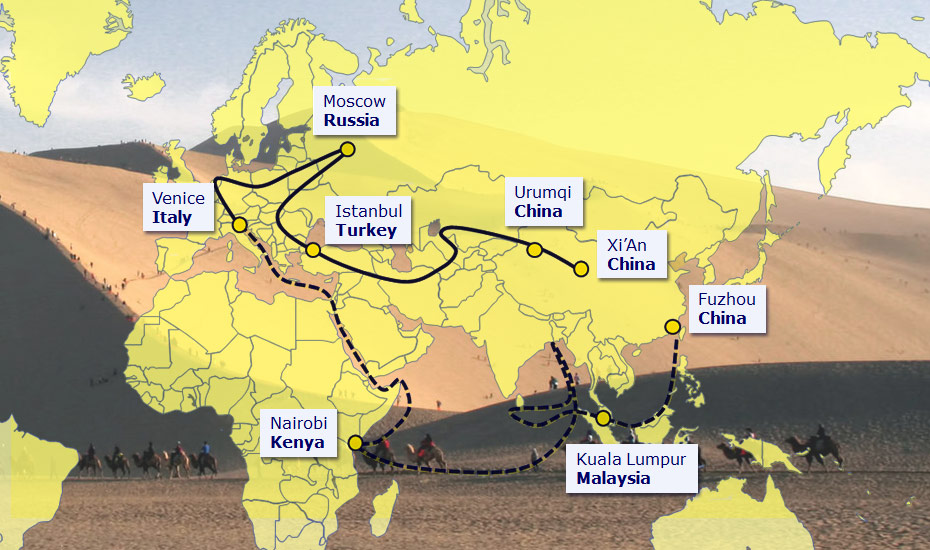

At the heart of One Belt, One Road lies the creation of an economic land belt that includes countries on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East and Europe, as well as a maritime road that links China’s port facilities with the African coast, pushing up through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean.

The project aims to redirect the country’s domestic overcapacity and capital for regional infrastructure development to improve trade and relations with Asean, Central Asian and European countries.

Historical roots

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes, formally established during the Han Dynasty. The road originated from Chang’an (now Xian) in the east and ended in the Mediterranean in the west, linking China with the Roman Empire.

The Silk Road was a network of trade routes, formally established during the Han Dynasty. The road originated from Chang’an (now Xian) in the east and ended in the Mediterranean in the west, linking China with the Roman Empire.

As China’s silk was the major trade product, German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coined it the Silk Road in 1877. It was not just one road but rather a series of major trade routes that helped build trade and cultural ties between China, India, Persia, Arabia, Greece, Rome and Mediterranean countries.

It reached its height during the Tang Dynasty, but declined in the Yuan dynasty, established by the Mongol Empire, as political powers along the route became more fragmented. The Silk Road ceased to be a shipping route for silk around 1453 with the rise of the Ottoman Empire, whose rulers opposed the West.

Rolling out the red carpet

Making friends

The Asia Development Bank estimates that Asia needs US$8tn to fund infrastructure construction for the 10 years to 2020. China well knows its development is linked to Asia and beyond and, in part, is banking its future on responding to its neighbours’ huge infrastructure needs via One Belt, One Road.

Meanwhile, China’s growing domestic market means the chance for the region and the world to capitalise by providing goods and services. The initiative is not without its challenges; cooperation and coordination with partner countries over the long term are paramount for it to be a lasting legacy.

Key to One Belt, One Road’s success is the development of an unblocked road and rail network between China and Europe. The plan involves more than 60 countries, representing a third of the world’s total economy and more than half the global population. We have ranked each country’s relationship with China from 1 to 5 based on political, economic and historical factors. China’s ultimate goal is to extend the initiative to Africa and Latin America.

Key to One Belt, One Road’s success is the development of an unblocked road and rail network between China and Europe. The plan involves more than 60 countries, representing a third of the world’s total economy and more than half the global population. We have ranked each country’s relationship with China from 1 to 5 based on political, economic and historical factors. China’s ultimate goal is to extend the initiative to Africa and Latin America.

Strategic agreements

There are compelling geopolitical reasons, such as energy security, for China to push forward with its One Belt, One Road plans at a time when its trading partners are potentially excluding it from strategic agreements.

Trans-Pacific Partnership countries, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the EU-Japan agreement show comprehensive liberalisation agendas, but do not include China and have the potential to increase trading costs.

In response, China plans to negotiate free-trade agreements with 65 countries along the OBOR. Until now China has signed 12 free-trade agreements including Singapore, Pakistan, Chile, Peru, Costa Rica, Iceland, Switzerland, Hong Kong and Taiwan and a further eight are under negotiation with Japan, Korea, Australia, Sri Lanka, Norway, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Asean and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Some worry that China has ulterior motives for naval expansion and energy security. What the sceptics miss is that securing economic growth is at the core of national security, as it legitimises the party’s rule. To ease worries, President Xi Jinping has emphasised “Three Nos”

Some worry that China has ulterior motives for naval expansion and energy security. What the sceptics miss is that securing economic growth is at the core of national security, as it legitimises the party’s rule. To ease worries, President Xi Jinping has emphasised “Three Nos”

- No interference in the internal affairs of other nations

- Does not seek to increase the so called “sphere of influence”

- Does not strive for hegemony or dominance

Domestic Silk Road Plan

One Belt, One Road could have as much impact on China’s internal economy as it will have internationally. China’s top priority is to stimulate the domestic economy via exports from industries with major overcapacity such as steel, cement and aluminium.

Many will be build-transfer-operate schemes in which large SOEs will lead the way, but smaller companies will follow. The domestic plan divides China into five regions with infrastructure plans to connect with neighbouring countries and increase connectivity.

Each zone will be led by a core province: Xinjiang in the Northwest, Inner Mongolia in the Northeast, Guangxi in the Southwest and Fujian on the coast.

Such a vast project will need funding

One Belt, One Road’s vast scale has elevated it to high-profile status given China’s financial resources. But even China’s deep pockets have limits, with the country’s total debt to GDP at 250%. Three financial institutions have been set up to support its development, which have met some resistance in the West given they provide alternatives to the World Bank, IMF and ADB.

Silk Road Infrastructure Fund

Asian Infra Investment Bank

New Development Bank