Written by Lauren Wolfe, read by Kelly Burke and produced by Jessica Beck. The executive producer was Max Sanderson

Fri 11 Nov 2022 05.00 GMT Last modified on Fri 11 Nov 2022 17.40 GMT

Across the country, fact-finding teams are tirelessly gathering evidence and testimony about Russian atrocities, often within hours of troops retreating. Turning this into convictions will not be easy, or quick, but the task has begun

- Read the text version here

- LIsten here

***

A mass burial site in Izium, Ukraine. Photograph: Vyacheslav Madiyevskyy/Ukrinform/ NurPhoto/ Rex/ Shutterstock

Ukraine’s true detectives: the investigators closing in on Russian war criminals

Across the country, fact-finding teams are tirelessly gathering evidence and testimony about Russian atrocities, often within hours of troops retreating. Turning this into convictions will not be easy, or quick, but the task has begun

by Lauren WolfeThu 20 Oct 2022 06.00 BST

On 8 March, two weeks into the war in Ukraine, Yanina Chmunevich stood in her grassy garden in Bobryk, 35 miles north-east of Kyiv, smoking a cigarette. As it burned to the filter, she counted 87 Russian heavy armoured vehicles going by, including earth-moving equipment, trucks, armoured personnel carriers and cars with long-barrelled guns attached. The next day, she watched the Russians bring in rocket launchers.

Three months later, Chmunevich, 39, who had worked at a petrol station before the war, was steadily recounting the details of the occupation of Bobryk as she sat on a sun porch in a plaid shirt and pink socks. A Ukrainian human rights investigator, Maryna Slobodianiuk, listened intently as she spoke. Slobodianiuk, 40, is a slight woman with a pouf of rust-coloured hair and a voice so quiet that you have to lean in close to hear her properly. But her mild manner is deceptive: as the head of investigations at Ukrainian nonprofit Truth Hounds, researching war crimes and crimes against humanity, she has been to the frontlines in Donetsk, Mykolaiv and Kharkiv, enduring constant bombardment, to record the stories of traumatised survivors.

Chmunevich described a visit from Russian soldiers in March. The men – who Chmunevich identified by their accents as Chechens or Armenians – lined her and four of her relatives up along a wall, confiscated their phones and asked for water. The family had already deleted their social media accounts in case there was anything pro-Ukrainian the Russians could find.

Throughout her recounting, Chmunevich slouched in a wooden chair and spoke in flat tones, her recitation almost mechanical. Like many Ukrainians I met during my three weeks in the country, after repeated questioning by journalists and investigators, she described terrifying events in a way that made them sound as bland as a discussion of the weather.

Advertisement

Her husband asked the Russians why they had come to Ukraine.

“To kill Zelenskiy and the Nazis,” one of them replied.

The Russians were in Bobryk for three weeks. While they were there, a group of Russian soldiers had taken over a neighbour’s property. Chmunevich had been able to watch them through narrow gaps in her boarded-up windows. She described hearing explosions from the direction of a nearby lake. She had heard from neighbours that the town’s mayor and a shop owner had been kidnapped, led away with plastic bags over their heads. Both men had endured beatings. The shop owner was later shot in the arm. He was told his crime was to have had a security camera at his store. It did not seem to matter that the camera wasn’t working.

Since the start of the invasion in February, three Truth Hounds investigators have been crisscrossing the country, recording first-hand accounts and documenting evidence of atrocities in line with the standards of the international criminal court (ICC) in The Hague, with which they remain in constant touch. They began their work in 2014 when the Russians invaded Crimea, but the very fact that Slobodianiuk was able to gather information in areas so recently occupied, and in such detail, is a unique aspect of this war. The international media, too, has had unprecedented access. As I observed the interview on Chmunevich’s porch, on the outer ring of watchers was a documentary team from a Turkish news channel.

Advertisement

“This is the most-covered war probably in history – by journalists, but also by these missions of investigators coming from every country in Europe and the ICC,” said Tetiana Pechonchyk, the head of the board of Zmina, a Kyiv-based media and human rights advocacy organisation. Zmina is part of a consortium of more than a dozen Ukrainian NGOs called the 5am Coalition. The Russians invaded at 5am on 24 February, and Ukrainians I met referred to it constantly.

Pechonchyk, an authority on war crimes, wore a red suit and matching lipstick when we met at a fish restaurant in Kyiv in July. She acknowledged this war has received “unprecedented attention”, and yet, “given the scale of atrocities”, she said, “it’s not enough. The war is ongoing, and every day the prosecutor’s office registers 100 or 200 more cases, and that doesn’t even include information from occupied areas.” As of 22 September, the prosecutor’s office had 34,000 cases filed, every one of which must be investigated, according to Ukrainian law. However, matching and corroborating information from even meticulous investigations is a process that will take years.

There may never have been a war so thoroughly scrutinised as it unfolds. Investigators move in as soon as the Russians leave, within 24 to 48 hours. The country has a more-or-less functioning judiciary, unlike, for instance, Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, where any semblance of a previously existing court system was obliterated during the three months of violence. The question remains: will all this evidence-gathering in Ukraine actually lead to convictions in a tolerable time frame, and will any of it be enough to implicate the people at the top of the command structure?

For now, Truth Hounds, along with dozens of other groups, are collecting evidence of soldiers’ actions on the ground. In Bobryk, Chmunevich told Slobodianiuk that the soldiers had shot and killed at least two villagers who were fleeing in their cars, beat and killed another who was held in a basement and interrogated her 50-year-old friend, knocking her front teeth out with a rifle butt. Eleven days after the Russians’ first visit, more soldiers returned to Chmunevich’s house, again lining the family up along a wall and checking their passports. They taunted and threatened the civilians, Chmunevich said, and appeared to be under the influence of alcohol or drugs. “They spoke slowly,” she said. “Their eyes looked strange, and their movements were slow.” She went on to describe them as “kids with guns”, no more than 25 years old, cockily clicking the catches of their guns on and off as they taunted the residents.

“Can you tell me what they said?” Slobodianiuk asked.

“They said if they went into the house and found even one phone, they would choose who to shoot,” Chmunevich recalled. As the soldiers were leaving, one of them had threatened her husband: “One of them said: ‘Why are we leaving and not shooting anyone? Let’s at least shoot him or the dog.’”

Advertisement

After an hour of questioning, Slobodianiuk thanked Chmunevich for her testimony and asked her to sign a form giving consent to share her statement with partner organisations, international courts, investigating bodies in Ukraine, the media and archival institutions.

We left through a gate in the wall that surrounds the property. Slobodianiuk told me what she found useful in the woman’s account. As well as the numbers of dead, detained and tortured in Bobryk, she was interested in detailed descriptions of the soldiers: the uniforms, the insignias, how they looked, their accents. “This helps us to identify at least the military unit they belong to,” she said. She could then follow up to ascertain which particular units were operating in the areas where crimes had been reported, and even return to villages with photos of alleged perpetrators for identification.

Slobodianiuk folded herself into my car. She explained that while there will ultimately need to be a broader picture assembled of Russian aggression, for her and her team, this is not their goal. Their realm is the grinding fieldwork, the knocking on doors, the questioning and reinterviewing of witnesses and survivors, and picking through unexploded ordnance for evidence. “The main idea is to find these criminals, the people who did these awful things,” she said.

In Kyiv, I met Yuriy Byelousov, 45, the head of war crimes in the office of the Ukrainian prosecutor general. Byelousov, who was dressed in all black, put his feet up on the table, exuding confidence bordering on swagger, and laid out the enormity of the task ahead. When we spoke, something like 18,000 cases had already been filed with his office, and Byelousov looked at his watch and joked that there had probably been another 100 filed since we’d been sitting there. There are only 8,000 prosecutors in the country, he said, most of whom have no specialised training in war crimes.

Ukrainian investigators are using drone footage as well as social media to build a more complete picture of Russia’s war crimes. Byelousov has been getting technical support from the US, France and the UK, among other countries: “The best possible world expertise is here right now,” he said. But the most daunting task is simply trying to impose order on the chaos: organising the deluge of intelligence being given to the office, dividing up responsibilities and avoiding duplication. When we met, just a month after he’d started the job, Byelousov told me he’d largely been focused on updating the office’s technology. He had implemented a scanning system for evidence that feeds into a central database. Drones and 3D scanners are being used to make models of the destruction of buildings, neighbourhoods and towns.

Advertisement

One critical component of the prosecutor general’s work involves liaising with the international experts advising on and auditing its cases, such as a joint UK-US-EU atrocity crimes advisory group. They can see what’s been gathered and judge its usefulness based on their knowledge of international standards. “They would advise us, ‘OK guys, you forgot this and this, correct this and that,’” Byelousov said.

Byelousov also spoke of close cooperation between his office and six nearby countries: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic. Investigators from these countries, Byelousov said, are willing to go to the eastern front: “These guys are pretty brave, you know, if they’re ready to go into another country and do this work.”

Efforts in Ukraine are bolstered by a wider global network of investigators decoding and corroborating satellite imagery and audio intercepts in order to collate evidence for future prosecutions. The network includes investigative journalism group Bellingcat and the UK-based human rights research organisation Centre for Information Resilience. “It’s going to be the nature of conflicts going forward, where there’s going to be this kind of network of accountability,” said Eliot Higgins, the founder of Bellingcat, which has previously tracked the use of chemical weapons in Syria and identified suspects in the 2018 novichok poisonings in Salisbury.

Byelousov was concerned that in some cases, the proliferation of citizen fact-finders and journalists on the ground has made things harder for survivors. He said he hopes that if someone has found evidence of sexualised violence, they would “just give it to us and don’t interview victims of rape for several hours. Then comes the journalist, and someone else, so when we come to the victim, [they have been] tortured 1,020 times.”

Advertisement

One international war crimes investigator agreed that such repeated questioning not only is traumatic for survivors, but can also affect the usefulness of their testimonies. “You don’t want witnesses who’ve told their stories over and over,” they said. “If there are inconsistencies, they can be ruled out or called ‘complicated witnesses’. It’s unfortunate.”

The process of bringing cases to court can be long and drawn-out, as with the prosecution of former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević. The Hague established the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1993 during the Bosnian war, but only charged Milošević in 1999. It took until 2001 to apprehend him and transfer him to The Hague for trial. Milošević died in a jail cell in 2006, while his trial was still under way.

The ICC was set up in 2002 to prosecute the leaders behind the worst atrocities, but the vast majority of cases arising from this conflict will be crimes committed by lower-ranking soldiers, which will be tried within Ukraine. Slobodianiuk thinks the ICC is “very precise but rather slow”. And being slow, she said, “means you are at great risk of losing evidence that is focused on high commanders”. Not only does physical proof, such as rocket fragments, disappear with time, but victims and witnesses change their minds about speaking to investigators. They move, they rebuild, they forget. “We have to pick everything up quickly to create the complete and true picture,” she said.

The most serious cases may be brought via the principle of universal jurisdiction, in which a third country steps in to try crimes that “are of such exceptional gravity that they affect the fundamental interests of the international community as a whole,” says the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights. (In January, a former Syrian security official, Anwar Raslan, was convicted in a German court for crimes against humanity.) But with so many perpetrators, inevitably, most do not face justice. For many Bosnian women who were raped by soldiers during the war, their ordeal continues, because their rapists walk free. They are liable to meet their attackers on city buses or crossing the street at night. In Rwanda, people live next door to the men who tortured them and killed their relatives.

Even the ICC, since its founding in 2002, has only ever convicted five men of war crimes or crimes against humanity, all high-level commanders: three from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one from Uganda and one from Mali. It’s why so many experts are pinning their hopes on Ukraine – it may be possible to convict more perpetrators in this war than ever before.

Afew days before I met Byelousov, Ukraine’s top war crimes prosecutor, I spoke to a nurse in her mid-50s, who I’ll call Svitlana Mazurko. Mazurko, who wore short-sleeved scrubs dotted with what looked like a cross between Giotto’s cherubim and the Powerpuff Girls, had survived the occupation of Bucha, a north-western suburb of Kyiv, in the early days of the war.

Advertisement

On the morning of 24 February, Mazurko recalled, she was at home in Bucha, cooking breakfast and doing laundry. Her husband, an engineer at the nearby Antonov airport in Hostomel, was at work. At 11.05am precisely, she remembers, she went on to the balcony to smoke. She heard low-flying helicopters – they were level with the second or third floor of her building – and watched as two jets swooped in behind them. At her count, she saw 40 helicopters heading toward the airport.

The jets, she said, made a couple of circles, strafing the suburban streets. As she recalled watching people duck and hide, she rubbed her knees with shaking hands. She remembered calling her daughter in Kyiv to tell her she should evacuate. Her husband wasn’t answering his phone. At noon, he finally called.

“I’ve been captured,” he said.

After he got to work, Russian soldiers had dropped to the ground from helicopters, rounded up the airport staff, and told them they were now hostages. For an hour, the captives watched as the soldiers discussed what they should do with their charges. It seemed that these men – mostly young, some drunk, pulled from the far reaches of Russia to fight in Ukraine – didn’t know what to do next.

Mazurko’s husband called again that afternoon. He had managed to negotiate his release, along with about 150 others at the airport. He made it home safely, but the shooting and shelling did not stop. Mazurko and her husband, with a few neighbours, moved down to the basement of their house.

Then, on 28 February, Mazurko said: “We had guests. The Russians came to us.”

Advertisement

Several cars arrived, and an armoured personnel carrier. From then, she said, “time flowed differently”. Her tears finally started to fall while she scrunched a tissue until it became useless. “They started looting in our building and had crowbars they used to open doors. We heard them shouting to one another.”

The area around Bucha is heavily wooded. A lot of local men go hunting and keep guns. The Russians went from house to house stealing rifles, as well as any gold they could find, canned meat, electrical appliances and even fishing rods. At one point in the weeks she spent under Russian occupation, Mazurko watched as a huge, refrigerated truck normally used to transport chicken meat was loaded up with the town’s possessions.

Mazurko and her family and neighbours were still hiding in the basement when she heard the soldiers shouting: “Who’s there? Hands in the air!”

About 30 soldiers put the women up against a wall with their arms up. “They were touching us everywhere with their hands,” Mazurko said. They forced the men to strip to their underwear. They were checking for military tattoos or marks on the men’s shoulders from rifle recoil. Men who have them, I’d been told, are singled out to go to “filtration camps”, from which they’re likely to be sent on to Russia, beaten or killed.

After weeks in her basement, Mazurko was so stressed that some of the blood vessels in her face ruptured. She and her neighbours had buried a man who’d died – apparently of a heart attack – while in the basement.

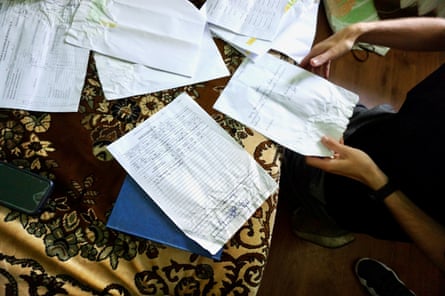

After we had talked for about an hour, Mazurko left the room and came back carrying a wrinkled plastic shopping bag, the kind with reinforced handles. It looked heavy. She came over to the couch and dumped out a stack of papers, as well as a hardcover book the colour of blue jeans. It had an unbroken seal on it. She said that her husband had found them at the airport after the Russians left. There were pages and pages of Russian documents, including an evacuation map to Belarus with coordinates of stops along the way, code names of officers and, in the blue book, the pencilled-in names, addresses and parents’ names – even the schools they attended – of each man in one of the anti-tank guided missile units that had landed at Antonov airport, which the Russians had hoped to use as a base to take Kyiv.

Sign up to The Long Read

Free weekly newsletter

Lose yourself in a great story: from politics to psychology, food to technology, culture to crime

https://www.google.com/recaptcha/api2/anchor?ar=1&k=6LdzlmsdAAAAALFH63cBVagSFPuuHXQ9OfpIDdMc&co=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cudGhlZ3VhcmRpYW4uY29tOjQ0Mw..&hl=vi&type=image&v=jF-AgDWy8ih0GfLx4Semh9UK&theme=light&size=invisible&badge=bottomright&cb=btz67iso5uvfPrivacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Advertisement

“Have you shown these to anyone before today?” I asked Mazurko.

She said she had not. Various war crimes investigators I spoke to said that proving the authenticity of such documents is key, so it was important that they did not get passed around from one person to the next, and there was no risk they could have been altered. “You have to take them home and not move them again until you hand them straight to the prosecutor-general’s office,” I told her.

When I showed photos of the documents to Byelousov, he was delighted. “Yeah, Russians, thanks!” he laughed. The documents, he said, had many potential uses. The most urgent thing was to get the physical documents directly to his office. They would also need to interview Mazurko’s husband to find out exactly where he’d found them. I would spend the next two weeks trying to make sure this cache of valuable data got into the right hands.

Among the documents I’d been given was a list of all the medical staff attached to various battalions’ tactical groups, as well as the call signs of each commander in the medical units. These could be compared with radio intercepts as a way to locate where the units were, and when. There was also an order for a huge amount of a heavy, Russian-made opioid anaesthetic that doctors and investigators have told me may be used to help with hangovers.

I showed Maryna Slobodianiuk from Truth Hounds photos of the documents. After a minute of flipping through the images on an iPad, she threw her head back and laughed. It was just insane, she said, to find such things. The hardcover personnel book would be particularly helpful, she said, because it lists the contract terms for each soldier, some of which expired before the invasion. This could indicate forced conscription, or exclude men from actually being in Ukraine with that unit during this war.

When I spoke to Slobodianiuk about a month later, she told me she had uploaded all the information I gave her to the Truth Hounds database, helping the group make as complete a profile of each listed Russian soldier as possible. “And if we can,” she said, “we’ll be able to link a specific crime to a perpetrator, and we will already have them in this database.”

Advertisement

When Pierre Vaux, an investigator at the Centre for Information Resilience (CIR), saw the hardcover “attendance” book I’d been shown, he couldn’t contain himself: “God, this is actual gold!” he said. The book, he believes, is a standard record book. He was able to use one of the documents to verify which troops were in what type of vehicle, and where, by looking at time-stamped satellite images (when cloud cover permitted) and painted-on vehicle numbers.

Even the smallest and strangest things the Russians left behind in their hasty withdrawals may be useful. A journalist for the Associated Press (AP) was shown a soldier’s letter home, found by police in Ozera, north-west of Kyiv. It had been written on the back of a scrap of paper – a blank sheet to record orders for the crew of BTR-MDM (an amphibious armoured personnel carrier) number 122. The AP reporter showed the paper to Vaux, who then entered the document into his database. Then he used the list of Russian medical staff attached to battalion tactical groups to identify two of the crew members in that vehicle, and the brigade they were part of – the 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade, based in Ulyanovsk – thus putting specific soldiers at a precise place.

He identified the evacuation route map as having been drawn pre-invasion, conjured from “wishful thinking”. It showed intended targets – many never taken – for occupation. The map’s starting point, the Vasylkiv airbase, is much farther south than the Russians ever reached, about 25 miles south-west of Kyiv.

It was further evidence that the Russian army was poorly briefed and ill-prepared for the invasion.

“It’s really like the back-of-a packet-of-cigarettes kind of map,” Vaux said. “A back-of-an envelope job.”

Documenting individual crimes and bringing the perpetrators to justice is one thing, but the ultimate goal of many war crimes investigators in Ukraine is to build a case against Russia for genocide. Putin views Ukraine as a Soviet-era creation, denying its long history as a separate region from Russia, and every person from a Ukrainian NGO I spoke to has collected evidence that cultural erasure and the obliteration of Ukrainian identity is Russia’s final aim. “Russians have a precise aim of destroying our culture, as part of our identity, as something that distinguishes Ukraine from Russia,” Olha Honchar, co-founder of Ukraine’s Museum Crisis Center, told Bloomberg News. Since the war began in February, about 500 cultural heritage sites have been damaged – a scale of such crimes not seen since the second world war, according to Kateryna Chuieva, Ukraine’s deputy minister of culture and information policy.

Advertisement

Genocide, first named as such in 1944 by a Polish lawyer, was recognised as a crime by the UN general assembly in 1946. A UN convention defines genocide as consisting of mental and physical crimes “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” including a deliberate attempt by the enemy to obliterate cultural heritage and reproductive capacity.

Tetiana Pechonchyk from Zmina said she had heard about cases of women being told by Russian soldiers while they were being assaulted: “We will rape you until you won’t want to see men any more.” In Rwanda, rape was often accompanied by mutilation – a way to forcibly sterilise the “less than human” enemy. In Bosnia, during the 1992-1995 war, Serbian soldiers held women at “rape camps” – places such as hotels or encampments where women were imprisoned until they became pregnant. A Ukrainian legal expert, Larisa Denysenko, is representing nine women in a number of lawsuits, seven of whom were gang raped by Russian soldiers in Kyiv, Sumy, Donetsk, Kherson and Chernihiv. She told me she believes “this is a military tactic of the occupation army, a method of terror and intimidation of the civilian population”. All nine women had heard Russians saying during their attacks: “banderivka” (fascist), “Nazi” and “prostitute”. In several cases, the women were raped in the presence of relatives who were held at gunpoint.

While Pechonchyk said she believes rape is happening on a “massive scale”, and that a number of organisations are collecting evidence, “we cannot assess it by numbers, as it is a hidden crime”. Not only are survivors often unwilling to talk about their attacks, she said many are living in occupied areas barely reachable by investigators. “It’s almost not possible to receive any information,” Pechonchyk said. “They might speak about torture, but not necessarily specifying what was done to them.”

In mid-October, the UN said it had documented more than 100 cases, and declared that rape is a “military strategy” used to dehumanise Ukrainians. “All the indications are there,” said Pramila Patton, the UN special representative on sexual violence. Patton spoke about cases of genital mutilation and Russian soldiers “equipped with Viagra”.

Advertisement

There is a growing body of evidence that Russians are trying to erase the Ukrainians through mass killing, forced Russian citizenship and the relocation of Ukrainians to Russia. Investigators are still discovering graves in Bucha, near Kyiv, and Izium in the east. They are finding signs of systematic, intentional murder: hands tied behind backs, bullet holes to the back of skulls.

“Russian authorities already announced that the children taken from Ukraine … don’t know Russian language on a sufficient level,” said Pechonchyk. “That’s why they need to adopt them and … make them Russian Russians.” She said that this is not the first time Russia has tried to “Russify” Ukrainians. During the 2014 Crimean war, all Crimeans were made Russian citizens. “This was also done by Stalin on a much larger scale in 1944,” Pechonchyk said, “when they accused Crimeans to be collaborators of Hitler and they deported people to Asia – to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and other countries.”

Byelousov told me his department was handing evidence of genocide to another body, but he would not say which. The ICC, for its part, would not confirm whether it is investigating genocide. In March, Karim Khan, the head of ICC prosecutions, put out a statement saying that the ICC would investigate and intended to prosecute attacks “intentionally directed” against civilians and “civilian targets”, including hospitals.

Ukrainians want justice for what they have endured, and for the loved ones they have lost. But, as Clint Williamson, the head of a joint US/UK/EU legal and investigative effort in partnership with the Ukrainians, told me, prosecutors “are not going to get their hands on people in the near term”. So far, just three Russian soldiers have been tried and convicted in Ukraine.

By the time I woke up on my last day in Kyiv, two missiles had already hit the city. Fired a little after 6am, they’d hit a kindergarten playground and a residential building, killing one man. I don’t know whether it was the sound of the strikes that roused me, or the calm lady from an app on my iPhone warning me that missiles had been launched towards my location and telling me to “pay attention”. About an hour later, a second air-raid alert, which blared through my phone as well as in the city streets, had already started up.

As the horns sounded, people remained where they were, in cafes, working, doing whatever they were doing. It’s exhausting to seek cover so many times a day, and the constant adrenaline shifts wreak havoc on the body. But with the hits being so close to my apartment, I threw on my body armour and went to sit in the stairwell. The idea is to get somewhere with two thick walls between you and the outside, and away from all glass. As I sat there, a cleaning woman casually entered my neighbour’s apartment with a stack of sheets and waved. Now I felt foolish.

Advertisement

In the evening, I visited an apartment building that had been hit. One civilian had been killed and six wounded. A few people I spoke to thought the old munitions factory across the road had been the intended target. Emergency workers slapped the soot from their heavy black coats, trimmed in reflective yellow, and checked their phones. Right in the centre of the massive apartment building, the top three storeys of eight were charred and crushed, as if a giant fist had smashed into it from the sky. Nearly every one of the hundreds of windows on the front of the structure were shattered.

Before I left Ukraine, I wanted to visit Babyn Yar, site of one of the worst single massacres of the second world war, where 33,000 Jews were killed. Later, another 70,000 people – including psychiatric patients, Soviet prisoners of war and Roma people – were murdered here. I stood in the gathering dark on the edge of a grassy field. To my left was a TV tower that looked like something out of a Russian constructivist painting, recently damaged by a Russian missile. There was nothing to do but stand and consider the bones beneath the soil – and the painful repetition of history.

There were 29 known survivors of the massacre at Babyn Yar. But a number of trials – some held in Kyiv, others in Nuremberg over the following 25 years – resulted in only about a dozen convictions of Nazis, most of whom had been living full and free lives in the meantime. (As late as 2021, a lawyer was pursuing a 99-year-old man said to be the last living perpetrator.) The attempt to cover up the mass murder at Babyn Yar means that only about one in 10 of the many thousands of people who died there have been identified. But much of what we do know was gathered by journalists who visited the site when Kyiv returned to Russian control in 1943. They interviewed three Russian prisoners of war who had survived the massacre, and they toured the site, finding bones and shoes and other remnants of the dead.

Bill Downs, who reported on the massacre for Newsweek, wrote to his parents in 1944: “Unless it can be brought home as to what the Germans have done in Europe – the cruelty and ruthlessness and bestial killings and emasculations and dismemberment that has gone on – well, I’m afraid that we’ll be too soft on them.”

It would take a few more decades, but memorials to the Jewish dead would be built on these killing fields. Reckoning for what is now happening in Ukraine will probably be slow to come, too, but the ground is already breached, exposing the crimes Russia is committing, every day, on Ukrainian soil. In Izium, investigators have identified 10 torture sites, including one at a police station, another at a school and another in a putrid hole in the ground, where Russians had run electric wires into men’s ears and hung them by the wrists. Survivors say they were waterboarded. And as investigators exhume hundreds of bodies from Izium’s sandy soil, they do so beneath some of the same conifer trees that had previously stood witness to mass murder during the second world war.

Unearthing the dead and witnessing evidence of their torture is a brutal and painstaking process. Many crimes will never be accounted for. Too much evidence has been destroyed already. But with so many people devoted to pursuing justice, and so much evidence collected, the probability is growing that there will be a price, of some kind, paid.

Additional research by Bill Meincke and Roona Korde-Samos

This article was amended on 31 October 2022 because an earlier version said only four people had ever been convicted by the ICC. In fact, 10 people in all have been convicted; of those, five were convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity. The others were convicted of offences against the administration of justice.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.