1. Quyết liệt đấu tranh với tội phạm mua bán bộ phận cơ thể người

2. Tham gia đường dây mua bán nội tạng người, cô gái trẻ bị khởi tố

***

Quyết liệt đấu tranh với tội phạm mua bán bộ phận cơ thể người

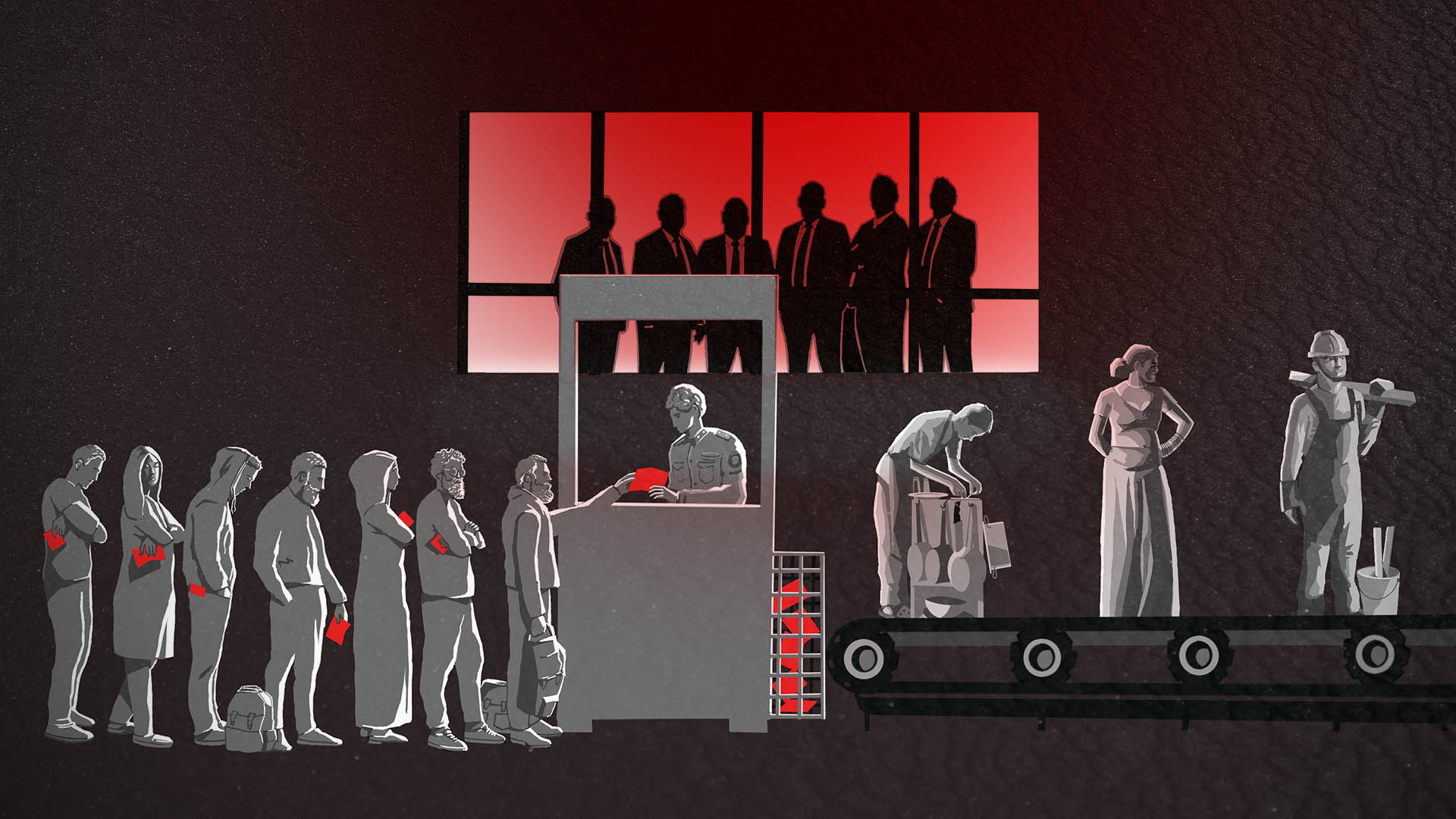

CAND – Do nhận thấy nhu cầu cao trong việc mua, bán bộ phận cơ thể người (gan, thận) để ghép cho các bệnh nhân đang mắc các bệnh mãn tính liên quan đến gan, thận, số tiền hưởng lợi chênh lệch lớn, các đối tượng đã nảy lòng tham, thực hiện hành vi môi giới mua bán bộ phận cơ thể người để hưởng lợi.

Tuy nhiên, hành vi tự ý bán nội tạng của bản thân là hành vi bị pháp luật nghiêm cấm, Cục Cảnh sát hình sự đã chỉ đạo Công an các đơn vị, địa phương tăng cường công tác tuyên truyền phòng ngừa, kịp thời phát hiện đấu tranh ngăn chặn, xử lý triệt để các hành vi vi phạm liên quan đến tội phạm này.

Mua 1 quả thận có giá trên 1 tỷ đồng

Theo thống kê của Cục Cảnh sát hình sự, liên tiếp trong thời gian vừa qua, một số phòng đơn vị nghiệp vụ của Cục phối hợp với Công an các đơn vị, địa phương đã liên tiếp triệt phá các vụ án liên quan đến mua, bán bộ phận cơ thể người (gan, thận).

Tiếp tục đọc “Quyết liệt đấu tranh với tội phạm mua bán nội tạng người”