Author(s): Timur Kuran

Conversations on Vietnam Development

By Raphael S. Cohen, the director of the Strategy and Doctrine Program at the Rand Corporation’s Project Air Force, and Gian Gentile, the deputy director of the Rand Corporation’s Army Research Division.

NOVEMBER 22, 2022, 1:36 PM

“Give diplomacy a chance.” This phrase gets repeated in almost every conflict, and the war in Ukraine is no exception. A chorus of commentators, experts, and former policymakers have pushed for a negotiated peace at every turn on the battlefield: after the successful defense of Kyiv, once Russia withdrew to the east, during the summer of Russia’s plodding progress in the Donbas, after Russia’s rout in Kharkiv oblast, and now, in the aftermath of Russia’s retreat from Kherson. The better the Ukrainian military has done, the louder the calls for Ukraine to negotiate have become.

And today, it’s no longer just pundits pushing for a negotiated settlement. The U.S. House of Representatives’ progressive caucus penned a letter to President Joe Biden calling for a diplomatic solution, only to retract it a short time later. Republican House leader Kevin McCarthy has promised to scrutinize military aid to Ukraine and push for an end to the war. Even Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley has reportedly pushed for Ukraine to negotiate, although he subsequently made clear that the decision should be Kyiv’s alone.

And why not negotiate? Isn’t a diplomatic solution the best—indeed, the only—option for any kind of long-term settlement between Russia and Ukraine? And if so, what could possibly be the harm in exploring those options? Quite a lot, actually: Despite the way it is commonly portrayed, diplomacy is not intrinsically and always good, nor is it cost-free. In the Ukraine conflict, the problems with a push for diplomacy are especially apparent. The likely benefits of negotiations are minimal, and the prospective costs could be significant.

First, the argument that most wars end with diplomacy and so, therefore, will the war in Ukraine is misleading at best. Some wars—such as the U.S. Civil War and World War II—were fought to the bitter end. Others—like the American Revolution, the Spanish-American War, World War I, or the First Gulf War—were won on the battlefield before the sides headed to the negotiating table. Still others—like the Korean War—ended in an armistice, but only after the sides had fought to a standstill. By contrast, attempts at a diplomatic settlement while the military situation remained fluid—as the United States tried during the Vietnam War and, more recently, in Afghanistan—have ended in disaster. Even if most wars ultimately end in diplomatic settlements, that’s not in lieu of victory.

60% off unrivaled insights.

Pushing Ukraine to negotiate now sends a series of signals, none of them good.

At this particular moment, diplomacy cannot end the war in Ukraine, simply because Russian and Ukrainian interests do not yet overlap. The Ukrainians, understandably, want their country back. They want reparations for the damage Russia has done and accountability for Russian war crimes. Russia, by contrast, has made it clear that it still intends to bend Ukraine to its will. It has officially annexed several regions in eastern and southern Ukraine, so withdrawing would now be tantamount, for them, to ceding parts of Russia. Russia’s economy is in ruins, so it cannot pay reparations. And full accountability for Russian war crimes may lead to Russian President Vladimir Putin and other top officials getting led to the dock. As much as Western observers might wish otherwise, such contrasts offer no viable diplomatic way forward right now.

Nor is diplomacy likely to forestall future escalation. One of the more common refrains as to why the United States should give diplomacy a chance is to avert Russia making good on its threats to use nuclear weapons. But what is causing Russia to threaten nuclear use in the first place? Presumably, it is because Russia is losing on the battlefield and lacks other options. Assuming that “diplomatic solution” is not a euphemism for Ukrainian capitulation, as its proponents insist, Russia’s calculations about whether and how to escalate would not change. Russia would still be losing the war and looking for a way to reverse its fortunes.

Diplomacy can moderate human suffering, but only on the margins. Throughout the conflict, Ukraine and Russia have negotiated prisoner swaps and a deal to allow grain exports. This kind of tactical diplomacy on a narrow issue was certainly welcome news for the captured troops and those parts of the world that depend on Ukrainian food exports. But it’s not at all clear how to ramp up from these relatively small diplomatic victories. Russia, for example, won’t abandon its attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure heading into the winter as it attempts to freeze Ukraine into submission, because that’s one of the few tactics Russia has left.

At the same time, more expansive diplomacy comes at a cost. Pushing Ukraine to negotiate now sends a series of signals, none of them good: It signals to the Russians that they can simply wait out Ukraine’s Western supporters, thereby protracting the conflict; it signals to the Ukrainians—not to mention other allies and partners around the world—that the United States might put up a good fight for a while but will, in the end, abandon them; and it tells the U.S. public that its leaders are not invested in seeing this war through, which in turn could increase domestic impatience with it.

Starting negotiations prematurely carries other costs. As Biden remarked in June: “Every negotiation reflects the facts on the ground.” Biden is right. Ukraine now is in a stronger negotiating position because it fought rather than talked. The question today is whether Ukraine will ultimately regain control over Donbas and Crimea, not Kharkiv and Kherson. This would not have been the case had anyone listened to the “give diplomacy a chance” crowd back in the spring or summer.

READ MORE

Why it’s still too soon for negotiations to end the war in Ukraine.

Ukrainian identity has been fundamentally changed by invasion.

There are plenty of reasons to believe that Kyiv will be in an even stronger bargaining position as time passes. The Ukrainians are coming off a string of successes—most recently retaking Kherson—so they have operational momentum. While Ukraine has suffered losses, Western military aid continues to flow in. Despite Russia’s missile strikes on civilian infrastructure, Ukrainian morale remains strong. By contrast, Russia is on the back foot. Its military inventories have been decimated, and it is struggling to acquire alternative supplies. Its mobilization effort prompted as many Russian men to flee the country as were eventually mobilized to fight in Ukraine. Moreover, as the Institute for the Study of War has assessed, “Russian mobilized servicemen have shown themselves to be inadequately trained, poorly equipped, and very reluctant to fight.”

By contrast, a negotiated settlement—even if it successfully freezes a conflict—comes with a host of moral, operational, and strategic risks. It leaves millions of Ukrainians to suffer under Russian occupation. It gives the Russian military a chance to rebuild, retrain, and restart the war at a later date. Above all, a pause gives time for the diverse international coalition supporting Ukraine to fracture, either on its own accord or because of Russian efforts to drive a wedge into the coalition.

Eventually, there will come a time for negotiations. That will be when Russia admits it has lost and wants to end the war. Or it will come when Ukraine says that the restoration of its territory isn’t worth the continued pain of the Russian bombardment. So far, neither scenario has come to pass. Indeed, the only softening of Russia’s position was Putin’s statement last month seemingly ruling out nuclear use—at least for the time being. Apart from that, the Kremlin seems intent on doubling down, even as its military continues to be slowly pushed out of Ukraine. That’s hardly an invitation to negotiate.

Might these arguments against the reflexive call for negotiations mean that war continues for months and possibly even years? Perhaps. But it’s not yet clear that there is a viable diplomatic alternative. And even if there was, it should be Ukraine’s choice whether or not to pursue it. Ukraine and its people, after all, are paying the price in blood. If the United States and its allies are sending tens of billions of dollars in military and economic aid to Ukraine, this is only a tiny fraction of what Washington has recently spent on defense and other wars. Thanks to the Ukrainians’ excellent use of this aid, the military threat from the United States’ second-most important adversary has been dealt a serious blow. The cold, if cruel, reality is that the West’s return on its investment in Ukraine seems high.

The harshness of these realities, however, does not make current calls for a negotiated settlement intrinsically moral. If diplomacy means ramming through a settlement when the battlefield circumstances dictate otherwise, it is not necessarily the morally more justifiable or strategically wiser approach. Sometimes fighting—not talking—is indeed the better option.

“To everything there is a season,” Ecclesiastes says, including “a time of war, and a time of peace.” There will come a time for diplomacy in Ukraine. Hopefully, it will come soon. But it doesn’t seem to be today.

Raphael S. Cohen is the director of the Strategy and Doctrine Program at the Rand Corporation’s Project Air Force.

Gian Gentile is the deputy director of the Rand Corporation’s Army Research Division.

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In.

| Top of the Agenda COP27 Ends With Landmark Deal on Loss and Damage The final deal of this year’s UN climate conference, COP27, included two historic firsts (Bloomberg): an agreement to establish a fund to help poor countries cope with climate damages, and a call for multilateral lenders such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to implement reforms ensuring that more of their funding addresses the climate crisis. The details of the loss and damage fund were left for future talks. Meanwhile, the communiqué left out proposed text on phasing down use of all fossil fuels, mentioning only coal. Negotiators were given an unusually short period of time to review the draft text on several major aspects of the communiqué, the Financial Times reported. After some delegates criticized the lack of transparency in negotiations, UN climate chief Simon Steill said he would review the summit process before next year’s conference to make it “as effective as possible.” |

| Analysis “The loss and damage deal agreed is a positive step, but it risks becoming a ‘fund for the end of the world’ if countries don’t move faster to slash emissions,” the World Wide Fund for Nature’s Manuel Pulgar Vidal tells the New York Times. “[The loss and damage agreement] tees up a big fight for next year’s Cop28 over who pays into and who benefits from the fund. Rich countries are pushing for China to chip in and finance to be targeted at ‘vulnerable’ countries,” Climate Home News’ Megan Darby, Joe Lo, and Chloé Farand write. This Backgrounder looks at the successes and failures of global climate agreements. |

Top of the Agenda U.S. Officials Say Russia Seeks to Buy Weapons From North KoreaNew U.S. intelligence shows Russia is seeking to purchase artillery shells and rockets (Reuters) from North Korea, American officials said yesterday. While Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations denied the allegations, White House spokesperson John Kirby said Moscow’s inquiry shows Russian President Vladimir Putin’s desperation amid the war in Ukraine. UN sanctions currently bar North Korea (AP) from selling weapons to other countries. It has attempted to strengthen relations with Russia since the start of the war and also expressed interest in sending workers to rebuild Russia-occupied territories in eastern Ukraine. Analysis “The only reason the Kremlin should have to buy artillery shells or rockets from North Korea or anyone is because Putin has been unwilling or unable to mobilize the Russian economy for war at even the most basic level,” the American Enterprise Institute’s Frederick W. Kagan tells the New York Times. Tiếp tục đọc “Council on Foreign Relations – Daily news brief Spet. 7, 2022” |

SÁNG ÁNH 19/08/2022 06:42 GMT+7

TTCT – Bao giờ chính trị mới hết sợ nhà văn, qua trường hợp Salman Rushdie lại vừa bị đâm ngay trên đất Mỹ?

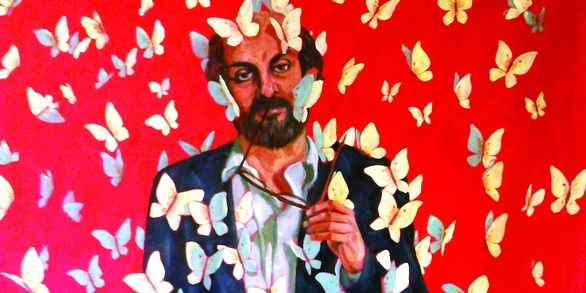

Salman Rushdie đã trở thành khuôn mặt đại diện cho tự do sáng tác trong một cuộc xung đột chồng chéo và phức tạp. Ảnh: PEN Canada

Cô ngồi một mình, áo hở rốn, coi dáng rất cô đơn tại quầy rượu mênh mông của khách sạn Atrium ở Praha. Lúc đó đã gần 2 giờ sáng, và hở rốn là vì cô mặc quốc phục sari của Bangladesh. Cô nhìn tôi và tôi đã định lại gần kéo ghế bên cạnh. “Khuya rồi, yên ắng nhỉ, bạn có thấy không, mọi thứ như là chùng hẳn xuống và 2 người mình vàng vọt như trong một bức tranh của Edward Hopper…”, tôi định nói.

Nhưng nào chỉ có 2 người mà là 3, và người thứ 3 cũng ngồi nhìn tôi là anh công an bảo vệ Taslima Nasreen làm tôi mất cả hứng. Năm đó, tại Hội nghị quốc tế Văn bút, nữ nhà văn này vì từ đạo Hồi và viết lách sao đó chống đối nên tính mạng bị đe dọa, và cũng như Salman Rushdie, bị một giáo sĩ treo án tử hình. Nhờ vậy nên mấy ngày trước tôi thấy cô đi xe BMW chống đạn đến đại hội, lúc nào cũng có một anh mặc đồ vest đi theo sau dáo dác. Tình hình rất là chán, tôi quyết định chỉ ủng hộ quyền tự do phát biểu và sáng tác của cô từ xa. Tôi gật đầu chào cô rồi đi ra khỏi khách sạn.

Những đụng độ văn chương, tôn giáo, tự do ngôn luận (và tự do sau ngôn luận) không bắt đầu hay kết thúc ở Salman Rushdie, nhưng với thế giới, nhất là phương Tây, thì văn sĩ 75 tuổi này lại trở thành bộ mặt cho cuộc tranh luận đó.

REMARKS

ANTONY J. BLINKEN, SECRETARY OF STATE

UN HEADQUARTERS

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

AUGUST 1, 2022Play Video

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Good afternoon. Secretary General Guterres, President Zlauvinen – thank you – Director General Grossi: Thank you all for your longstanding leadership on nonproliferation.

I noted that Prime Minister Kishida of Japan is here as well this morning, which sends a very powerful message. Earlier this year, he reaffirmed Japan’s commitment to nonproliferation in a joint statement with President Biden.

And a very special thanks to the foreign ministers, the deputy foreign ministers, the teams who have traveled to New York for these meetings and to get us off to a good start.

It’s great to be with you all here in person today, especially – especially – given the critical role the NPT has played in upholding the global nonproliferation regime.

More than five decades ago, at the height of the Cold War, representatives of 18 nations drafted the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

In the years that followed, nearly every country on Earth has joined the NPT.

Tiếp tục đọc “US State Secretary Antony J. Blinken’s Remarks to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference”July 26, 2022 3:41 PM VOA

Congolese protesters scale the perimeter wall of the compound of United Nations peacekeeping force’s warehouse in Goma, in the North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, July 26, 2022.”/>

The United Nations said that three of its peacekeepers were killed in ongoing anti-U.N. protests that turned violent in eastern Congo on Tuesday, while several civilians were also killed in the violence.

“At the MONUSCO Butembo base today, violent attackers snatched weapons from Congolese police and fired upon our uniformed personnel,” U.N. spokesman Farhan Haq told reporters at U.N. headquarters in New York.

MONUSCO is the acronym for the U.N. Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Protesters in Butembo, in the eastern province of North Kivu, accuse the U.N. of having failed to protect them from an escalation of violence from armed groups.

Tiếp tục đọc “UN Peacekeepers, Congolese Civilians Killed in Violent Protests”July 08, 2022

The need for peacebuiliding in post-conflict societies grew out of the realization that true and enduring peace requires more than just signing agreements to stop the fighting. But while many of peacebuilding’s objectives seem self-evident, it is often laborious and expensive—and easily undone. Learn more when you subscribe to World Politics Review (WPR).

French President Emmanuel Macron delivers a speech at the opening session of the Paris Peace Forum at the Villette Conference Hall in Paris, France, Nov. 11, 2018 (SIPA photo by Eliot Blondet via AP Images).

Tiếp tục đọc “How to make sure peace endures once the fighting ends”

Posted Fri 24 Jun 2022 at 9:06amFriday 24 Jun 2022 at 9:06am

Help keep family & friends informed by sharing this article

abc.net.au/news/sri-lanka-economic-collapse/101179714COPY LINKSHARE

Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister says the island nation’s debt-laden economy has “collapsed” as it runs out of money to pay for food and fuel.

Short of cash to pay for imports of such necessities and already defaulting on its debt, the country is seeking help from neighbouring India and China and from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, who took office in May, has emphasised the monumental task he faces in turning around an economy he said was headed for “rock bottom”.

Sri Lankans are skipping meals as they endure shortages and lining up for hours to try to buy scarce fuel.

It’s a harsh reality for a country whose economy had been growing quickly, with a growing and comfortable middle class, until the latest crisis deepened.

The government owes $US51 billion ($73.9 billion) and is unable to make interest payments on its loans, let alone put a dent in the amount borrowed.

Tourism, an important part of economic growth, has sputtered because of the pandemic and concerns about safety after terror attacks in 2019.

Tiếp tục đọc “How the Sri Lankan economy run out of money to pay for food and fuel”

foreignpolicy – JUNE 16, 2022, 5:16 PM

A 10-day world tour ended with a meeting of NATO defense ministers in Brussels.

By Jack Detsch, Foreign Policy’s Pentagon and national security reporter, and Robbie Gramer, a diplomacy and national security reporter at Foreign Policy.

|

BRUSSELS—NATO nations are preparing to significantly bulk up the 30-country alliance’s forces in Eastern Europe, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said today, part of a plan to stand tall in the face of Russia’s military revanchism as Europe faces its most serious security threat from the Kremlin since the Cold War with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“Russia’s aggression is a game-changer, so NATO must maintain credible deterrence and strong defense,” Stoltenberg said.

“This will mean more NATO forward-deployed combat formations to strengthen our battlegroups in the eastern part of our alliance. More air, sea, and cyber defenses, as well as prepositioned equipment and weapon stockpiles,” he added.

Tiếp tục đọc “Biden’s Defense Chief Puts Alliances at Center Stage of U.S. Defense”

| Daily News Brief May 27, 2022 |

| Editor’s note: There will be no Daily Brief on Monday, May 30, in observance of Memorial Day. |

| Top of the Agenda Blinken Details U.S. Strategy Toward ChinaU.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken laid out (CNN) the Joe Biden administration’s strategy toward China in a speech yesterday (State Dept.), calling Beijing “the most serious long-term threat to the international order.” Blinken said Washington is determined to avoid a conflict or new Cold War with China. The U.S. approach—called “invest, align, compete”—hinges on efforts to invest in domestic sources of strength, align with allies and partners, and compete with China on issues such as technological innovation. Blinken reiterated that the U.S. strategy toward Taiwan is unchanged, and that Washington seeks to engage and cooperate with China where possible, especially on climate change. Officials said President Biden could hold a phone call (Politico) with Chinese President Xi Jinping within weeks. |

MAY 08, 2022•STATEMENTS AND RELEASES The White House

###

Analysis by Stephen Collinson, CNN

(CNN)This was the week when the war in Ukraine truly transitioned from one nation’s bloody fight for liberation against Russia’s vicious onslaught to a potentially years-long great power struggle.

Every day brought a sense of grave, historic events and decisions that will not just decide who wins the biggest land war between two countries in Europe since World War II, but will shape the course of the rest of the 21st century.

President Joe Biden declared Thursday that two months of fighting in the war triggered by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion had brought the world to a critical point.

Tiếp tục đọc “A new realization dawns for Washington, Europe, Kyiv and Moscow”The Russia-Ukraine War could cost the global economy $950bn in 2022, but which countries will be hit hardest? ODI index ranks 118 LICs & MICs and finds Belarus, Armenia, Kyrgyz Republic & Lebanon are most vulnerable.

Longstanding ties and weapons sales to a number of countries in Southeast Asia insulate Russia from ASEAN criticism over Ukraine war.

Blog Post by Joshua Kurlantzick

March 8, 2022 4:08 pm (EST)

In recent years, Russia, which had not had much of a strategic or economic presence in Southeast Asia, has become a more involved player once again. It has cultivated close ties with Myanmar, regularly selling weapons to Myanmar and cultivating strategic ties. Particularly after the February 2021 Myanmar coup, when even Beijing seemed to have doubts about how the coup had destabilized the country and led to potential risks to China’s investments, Russia stood strongly behind the junta. Russian officials participated in a prominent military ceremony in Myanmar after the coup, Russian continued to supply large numbers of arms to the junta, even as it launched a scorched earth policy against coup opponents and ethnic minority groups, and the Kremlin invited junta leader Min Aung Hlaing to Moscow in June (before he had any major visits to Beijing), sending a strong signal of support to Naypyidaw.

Tiếp tục đọc “Russia’s Continuing Ties to Southeast Asia—and How They Factor Into the Ukraine War (3 parts)”