visualcapitalist January 19, 2026

Key Takeaways

China dominates global rare earth mining, but undeveloped reserves elsewhere could reshape future supply chains.

Greenland holds an estimated 1.5 million metric tons of rare earth reserves despite having no commercial production.

U.S. President Donald Trump has once again put Greenland at the center of global attention.

His renewed threat to assert U.S. control over the Arctic territory has drawn sharp reactions from European leaders and Denmark, which governs Greenland as an autonomous territory.

While the island’s strategic location is often cited, another underlying motivation is increasingly tied to its vast mineral potential. In particular, Greenland’s rare earth reserves have become a focal point in a world racing to secure critical resources.

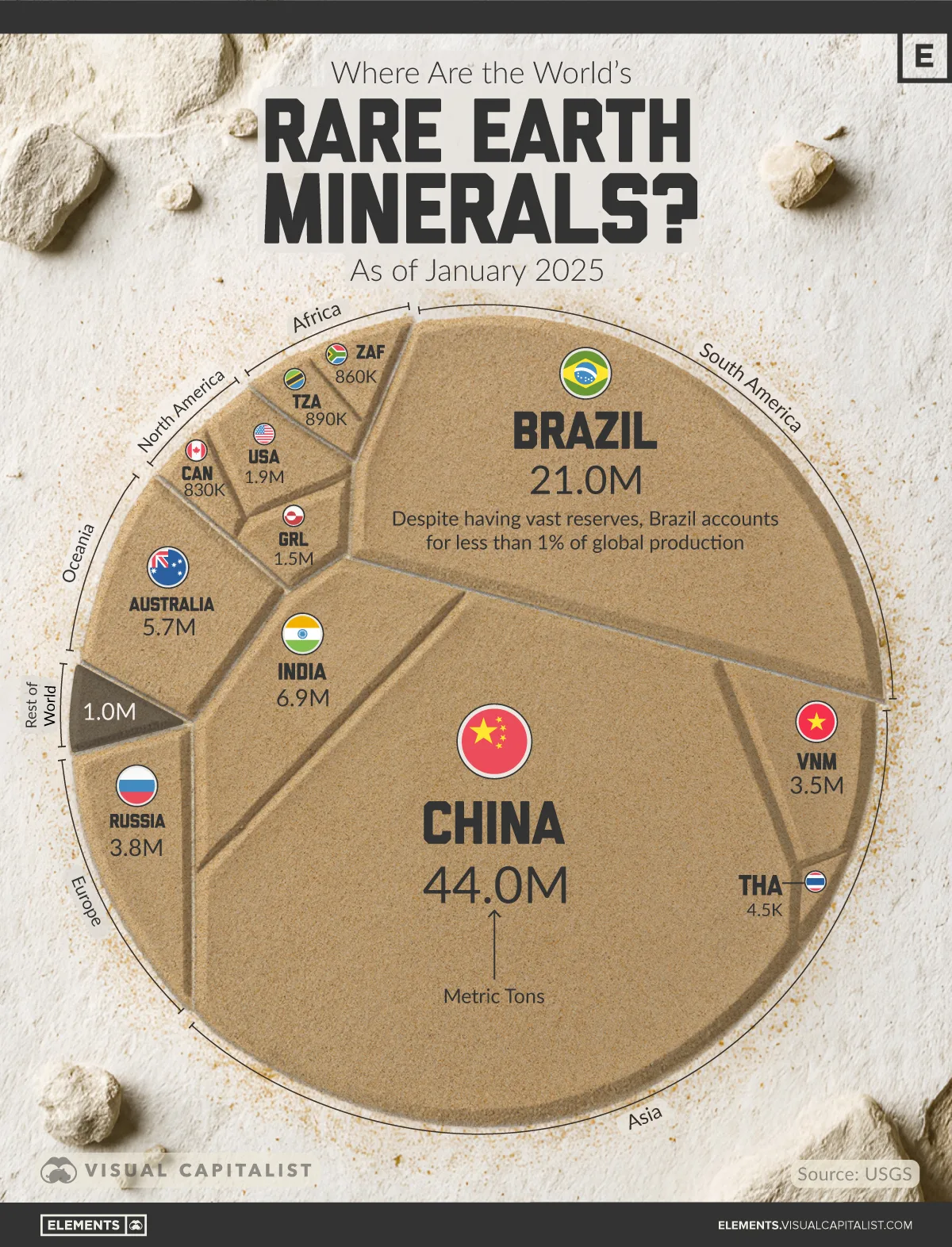

This visualization compares rare earth mine production and reserves across countries, placing Greenland’s untapped resources in a global context.

The data for this visualization comes from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), as of 2024.

China’s Grip on Rare Earth Supply

China remains the backbone of the global rare earth market. In 2024, it produced roughly 270,000 metric tons, accounting for well over half of global output.

China also controls the largest reserves, estimated at 44 million metric tons. This combination of scale and integration gives Beijing significant leverage over industries ranging from electric vehicles to defense systems.

| Country | Reserves (Metric Tons) | Rare Earth Production 2024 (Metric Tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 🇨🇳 China | 44.0M | 270,000 |

| 🇧🇷 Brazil | 21.0M | 20 |

| 🇮🇳 India | 6.9M | 2,900 |

| 🇦🇺 Australia | 5.7M | 13,000 |

| 🇷🇺 Russia | 3.8M | 2,500 |

| 🇻🇳 Vietnam | 3.5M | 300 |

| 🇺🇸 United States | 1.9M | 45,000 |

| 🇬🇱 Greenland | 1.5M | 0 |

| 🇹🇿 Tanzania | 890K | 0 |

| 🇿🇦 South Africa | 860K | 0 |

| 🇨🇦 Canada | 830K | 0 |

| 🇹🇭 Thailand | 4.5K | 13,000 |

| 🇲🇲 Myanmar | 0 | 31,000 |

| 🇲🇬 Madagascar | 0 | 2,000 |

| 🇲🇾 Malaysia | 0 | 130 |

| 🇳🇬 Nigeria | 0 | 13,000 |

| 🌍 Other | 0 | 1,100 |

| 🌐 World total (rounded) | >90,000,000 | 390,000 |

Large Reserves, Limited Production Elsewhere

Outside China, many countries with sizable reserves play only a minor role in production.

Brazil holds an estimated 21 million metric tons of rare earth reserves yet produces almost nothing today. India, Russia, and Vietnam show similar patterns.

Why Greenland Matters

Greenland’s estimated 1.5 million metric tons of rare earth reserves exceed those of countries like Canada and South Africa. Yet the island has never had commercial rare earth production.

Environmental protections, infrastructure constraints, and local political opposition have slowed development. Still, as supply chain security becomes a priority for major economies, Greenland’s position is becoming harder to ignore.

Trump’s interest in Greenland is driven by more than symbolism. Rare earths are essential for advanced manufacturing, clean energy technologies, and military hardware. With China firmly entrenched as the dominant supplier, policymakers in Washington are increasingly focused on alternative sources.