May — Aug 2023

By Ralph A. Cossa and Brad Glosserman

Published September 2023 in Comparative Connections · Volume 25, Issue 2 (This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 25, No. 2, September 2023. Preferred citation: Ralph A. Cossa and Brad Glosserman, “Regional Overview: Building Partnerships Amidst Major Power Competition,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp 1-24.)

CONNECT WITH THE AUTHORS

Tama University CRS/Pacific Forum

Major power competition was the primary topic du jure at virtually all of this trimester’s major multilateral gatherings, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continuing to serve as a litmus test—a test many participants struggled to avoid taking. It was clear which side of the fence the G7 leaders stood on; Putin’s invasion was soundly condemned and Sino-centric warning bells were again gently sounded. At the BRICS Summit and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (sans the US), those alarms were clearly muted, as they were at the ASEAN Regional Forum, at which foreign ministers from all three were present. Headlines from the IISS Shangri-la Dialogue focused on the meeting that did not occur, as China’s defense minister pointedly refused to meet with his US counterpart. At the ASEAN-ISIS’ Asia-Pacific Roundtable, participants lamented the impact of major power tensions on ASEAN unity, even though ASEAN’s main challenges are internal ones that predate the downturn in China-US relations. Meanwhile, Beijing and Washington both expended considerable effort at these and other events throughout the reporting period fortifying and expanding their partnerships, even as many neighbors struggled not to choose sides or to keep a foot in both camps.

Growing China-US Tensions

Academics continue to spend a great deal of time arguing whether a new Cold War is upon us—both the differences and similarities to the original US-USSR version are pretty obvious—but there is no disputing that tensions between Washington and Beijing have grown considerably over the past year or so, with the implications being felt not only in the Indo-Pacific neighborhood but globally. US allies are becoming more candid in expressing concerns about China’s current actions and long-term ambitions, even as many in Asia and the so-called “Global South” repeat their time-honored “don’t force us to choose” refrain.

In the great East-West or Democracy-Authoritarianism divide, support for Ukraine and/or a willingness to condemn the Russian invasion increasingly appears to be a litmus test, one that many attempt to evade out of fear of alienating Moscow and/or Beijing. Some like India and Vietnam do so as a result of security concerns. Both rely heavily on Russian military hardware (at least for now; India is looking to diversify). Others like the Central Asian “Stans” claim neutrality while fearing they could be next. Some countries (read: China) unconvincingly claim neutrality while clearly tilting toward Moscow, while some members of the Global South want to pick the pockets of both sides. As the old saying (Miles’ Law) goes, “Where you stand depends on where you sit.” The Ukraine “issue” becomes particularly challenge at multilateral meetings where both Americans/Westerners and China/Russia are present.

The G7 Revives

The first big multilateral event of this reporting period was the annual summit of the Group of Seven (G7) leading industrial nations, hosted by Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio in Hiroshima. We’ve been G7 skeptics, the symbol of a global order whose time has passed. Recently, however, the group has re-emerged as a vehicle for global governance, and Kishida deserves a good bit of the credit.

Figure 1 Leaders of the G7 member states in Hiroshima. Photo: Council of the European Union

When formed 50 years ago, G7 countries represented nearly two-thirds of global wealth. That figure has dropped to just 44% and its role as international economic manager has been eclipsed by the G20, formed in the wake of the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis. The invasion of Ukraine has given the group new urgency as its members seek to backstop an international order under assault, even as it has placed new challenges on G20 unity.

Kishida has made Ukraine the starting point for Japan’s chairmanship, and he has repeatedly declared that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is a concern for the entire world and its operating rules and principles. In the Leaders Declaration, the grandees pledged to

- support Ukraine for as long as it takes in the face of Russia’s illegal war of aggression;

- coordinate our approach to economic resilience and economic security that is based on diversifying and deepening partnerships and de-risking, not de-coupling;

- drive the transition to clean energy economies of the future through cooperation within and beyond the G7;

- launch the Hiroshima Action Statement for Resilient Global Food Security with partner countries to address needs today and into the future; and

- deliver our goal of mobilizing up to $600 billion in financing for quality infrastructure through the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII).

The first three priorities—resist unilateral attempts to redraw the status quo, promote economic security and resilience, and promote sustainable development—are repeated throughout the document.

While Russia is the immediate threat, China is clearly a concern. But China is not mentioned until the 51st paragraph, and the first four bullet points in that discussion emphasize cooperation with Beijing. It isn’t until the penultimate line of the 35th page that a “China threat” emerges. The leaders voiced concern about Beijing’s militarization of the Indo-Pacific, the stability of the Taiwan Strait, and its expansive territorial claims in the East and South China Seas. Yet G7 countries still balance competing interests when engaging China. They seek mutual economic opportunities and de-risking rather than decoupling.

Beijing was not happy with the resulting compromise. It charged the G7 with “hindering international peace, undermining regional stability and curbing other countries’ development,” and called in Japan’s ambassador to scold his government for attempting “to smear and attack China, grossly interfering in China’s internal affairs.”

Kishida’s decision to hold the meeting in Hiroshima, his hometown, reflected his determination to produce a clear unambiguous statement that denounces the use of nuclear weapons, especially for intimidation or in furtherance of national territorial ambitions. The Declaration promised “to strengthen disarmament and nonproliferation efforts, towards the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all.” As Kishida explained, “Hiroshima, once devastated by the atomic bombing, has rebuilt itself to become a city that seeks peace. I want the leaders of the G7 members and major countries of various regions to make efforts to demonstrate their commitment to peace that will go down in history in this city.” The leaders visited the Hiroshima Peace Park, laid wreaths at the cenotaph for victims of the atomic bomb, were briefed by Hiroshima Mayor Matsui Kazumi on the history of the Atomic Bomb Dome and the events of Aug. 6, 1945, and met Ogura Keiko, a survivor of the attack. The power of those events was balanced by the realist calculations—the reliance on nuclear weapons for deterrence and peace—that guide decision-making in G7 capitals.

Another priority is protecting countries from economic coercion. Both Russia and China have tried to use economic leverage for political gain, and the G7 declaration condemned such practices. The group launched the Coordination Platform on Economic Coercion to increase “collective assessment, preparedness, deterrence and response to economic coercion, and further promote cooperation with partners beyond the G7.” The leaders also released the G7 Leaders’ Statement on Economic Resilience and Economic Security, which focused on building resilient supply chains and resilient critical infrastructure, and called for joint action to combat economic coercion, harmful practices in the digital sphere, cooperating on international standards setting, and protecting critical technologies.

A key partner in those efforts is the developing world and the declarations underscored outreach to “the Global South” to promote economic resilience and development more generally. As ever, the words make much sense and deserve applause. But they mean nothing in the absence of efforts to promote shared security, growth, and prosperity.

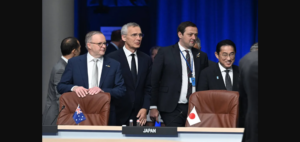

NATO Takes a Dip in the Indo-Pacific

Four regional leaders ventured to Vilnius, Lithuania in July for the annual summit of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This was the second consecutive year that the organization’s four major Indo-Pacific partners—Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea, referred to as the AP4—attended that meeting. Each of the four is working on an Individually Tailored Partnership Program (ITPP) that will upgrade relations and facilitate cooperation on issues such as maritime security cooperation, cybersecurity, new and emerging technologies, outer space, combatting disinformation and the impact of climate change on security.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at meeting with NATO’s Indo-Pacific partners during the NATO summit in July. Photo: Jacques Witt/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

Closer ties make sense in an age of “indivisible security” and the growing interest of European governments in the Indo-Pacific region. NATO’s most recent Strategic Concept, the document that guides planning and policy, was released last year and it noted that China’s stated ambitions and coercive policies “challenge our interests, security and values.”

There were reports during the spring that NATO might open a regional office in Japan, to facilitate contacts and implementation of those ITPPs. There has been support for closer ties from both Asian and European governments. Japan has been particularly assiduous in courting NATO. The office did not materialize, however, reportedly a result of French opposition: Paris wants NATO to remain focused on trans-Atlantic threats and challenges.

China wasn’t happy either. A foreign ministry spokesperson warned that “the Asia-Pacific does not welcome group confrontation, does not welcome military confrontation,” that NATO’s plan to develop a presence in the region “undermines regional peace and stability” and that countries in the area “should be on high alert.” China Daily editorialized that Japan’s support for that effort was making it the “doorman” of NATO.

In truth, NATO is unlikely to make a direct contribution to regional security. It is too far away and there are far more compelling needs closer to home. Still, the possibility of a European presence complicates an adversary’s planning and a united front of like-minded nations would support deterrence in other ways. They should not be undervalued.

Bigger May Not be Better for BRICS

Countering the G7 (at least in the minds of some of its participants) was the 15th BRICS summit that convened in late August in Johannesburg, South Africa. The BRICS—which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—seems to have adopted as its raison d’etre the revision of a world that does not afford its members the respect and influence they feel they deserve. As their Declaration explained, they are animated by the “BRICS spirit of mutual respect and understanding, sovereign equality, solidarity, democracy, openness, inclusiveness, strengthened collaboration and consensus.” They seek “a more representative, fairer international order, a reinvigorated and reformed multilateral system, sustainable development and inclusive growth.”

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, center, delivers the XV BRICS Summit declaration, flanked by, from left, President of Brazil Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, President of China Xi Jinping, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in Johannesburg, South Africa, Thursday, Aug. 24, 2023. Photo: AP

They were originally identified as a group of countries that were underestimated in assessments of global power and would, if their trajectories continued, exercise real influence. That potential remains potential for a variety of reasons. Nevertheless, the five countries still clamor for change and a greater say in the international system. Chinese leader Xi Jinping explained “Right now, changes in the world, in our times, and in history are unfolding in ways like never before, bringing human society to a critical juncture,” adding that “The course of history will be shaped by the choices we make.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin was angrier—understandably so, as he was prevented from attending because of an indictment issued by the International Criminal Court for actions in Ukraine and his South African hosts would have been obliged to arrest him if showed up. He condemned the West for domineering policies and hypocrisy, and countered that “We are against any kind of hegemony,” and accused the West of “continuing neocolonialism.’ He blamed “the desire of some countries to maintain this hegemony that led to the severe crisis in Ukraine.”

The BRICS resent dominance by the West and the imposition of Western values. That is a powerful attraction. Reportedly over 40 countries have expressed interest in joining the group and two dozen are said to have applied to join. At the end of the meeting, the group agreed to expand and Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were invited to join from the start of next year as the “first phase of the expansion process.” South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, meeting chair, added that other nations will join later.

Doubling the size of the group is ambitious and on paper the new members are impressive. They are big trading nations and that, as well as their desire to reduce US power and influence, encourages them to find alternatives to the dollar in international trade. That will not be easy, however, as most other nations have discovered over the last 50 years. No other currency is used as widely, is tradeable, and enjoys the trust of third parties.

In addition, expanding the group will make it even harder to find consensus. Their shared sense of grievance will not be enough to paper over tensions between, say, China and India, or Saudi Arabia and Iran. Delhi and Beijing are at odds over many issues, relations with Washington among them. Moreover, there is little appetite for the most ambitious agenda. Brazil’s president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, was more circumspect, saying “We do not want to be a counterpoint to the G7, G20, or the United States,” adding that “We just want to organize ourselves.”

Shanghai Cooperation Organization Expands as Well

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization, originally comprised of China, Russia, and four former Soviet Central Asia Republics (Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan), has also expanded in recent years to include Pakistan and BRICS member India, which served as 2022-23 chair and thus hosted this year’s SCO Summit on July 4. Since the meeting was held virtually, Putin was among the attendees. The Council of Heads of State of SCO issued a New Delhi Declaration which, unsurprisingly, made no reference to Ukraine even as it professed support for “non-interference in internal affairs and non-use of force or threats to use force” and the “peaceful settlement of disagreements and disputes.” Given its peace-loving nature, this year the SCO welcomed Iran as its ninth member.

ASEAN-led Multilateralism Overshadowed

Readers will be excused if they missed the meeting of regional foreign ministers as ASEAN convened the annual ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and associated side meetings in Jakarta in July, an event that has become largely overshadowed not only by the East Asia Summit (EAS) but by its own ineffectiveness in dealing with key regional security issues like Myanmar, the South China Sea, and North Korea’s missile and nuclear ambitions.

Figure 4 Various Foreign Ministers at the Asian Regional Forum in July. Photo: Association of Southeast Asian Nations

With foreign ministers from China, Russia, and the United States in attendance, the July 14 ARF session proved to be quite contentious. ASEAN struck a careful pose on Russia since it is seeking Moscow’s support for an initiative on food security at the EAS. Most ASEAN members maintain their own ties with Russia despite condemning its attacks on Ukraine, underscoring ASEAN’s “complex balancing act of pushing for peace in Ukraine without compromising key economic interests.”

The ARF Chairman’s Statement stated: “With regard to the war in Ukraine, as for all nations, the Meeting continued to reaffirm its respect for sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity. The Meeting discussed the war in Ukraine, and views were expressed on the recent developments and the need to address the root causes. The Meeting reiterated its call for compliance with the UN Charter and international law. The Meeting underlined the importance of an immediate cessation of hostilities and the creation of an enabling environment for peaceful resolution.”

The Statement was tougher when it came to Myanmar, not only reaffirming the importance of the largely-ignored Five Point Consensus, but strongly condemning “continued acts of violence, including air strikes, artillery shelling, and destruction of public facilities.” It called on “all parties” to “take concrete action to immediately halt indiscriminate violence, denounce any escalation, and create a conducive environment for the delivery of humanitarian assistance and inclusive national dialogue,” which the ruling junta will no doubt continue to ignore.

After two decades of discussions, China and ASEAN, during their bilateral side session, “edged closer” to agreeing upon a South China Sea Code of Conduct by instituting some guidelines aimed at preventing further deterioration of the security situation. The ARF Chairman’s Statement “welcomed the progress achieved so far in the ongoing negotiations on the Code of Conduct.” Forgive us if we don’t hold our breath.

Shangri-la Standoff

Tensions were also clearly in evidence at this year’s 20th Shangri-la Dialogue in Singapore in June, as highlighted by Beijing’s refusal to allow its Minister of National Defense, General Li Shangfu, from meeting bilaterally with US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, citing continuing US sanctions against Li and other senior Chinese officials. (Li was originally sanctioned by the Trump administration over his role in the acquisition of weapons from Russia.)

Austin, in his opening plenary address on “US Leadership in the Indo-Pacific,” focused primarily on America’s positive contributions to regional security but did, toward the end, complain about the “alarming number of risky intercepts” by Chinese aircraft against US and allied aircraft “flying lawfully in international airspace.” His final words reminded Beijing that the US “remains deeply committed to preserving the status quo in the strait, consistent with our long-standing One China policy and…will continue to categorically oppose unilateral changes to the status quo from either side.”

Li, in his separate plenary remarks on “China’s New Security Initiatives,” praised President Xi Jinping’s “win-win” Global Security Initiative and outlined China’s contributions to international peace and stability. He also noted China’s “objective and impartial stance” on the Ukraine “issue” – perish the thought that we might call it an invasion or war. Li addressed US-China tensions more directly and comprehensively, noting that “severe conflict or confrontation between China and the US will be an unbearable disaster for the world.”

In tine-honored Chinese fashion, Li generally avoided naming names, merely noting that “a major country should behave like one…instead of provoking bloc confrontation for self-interests” while accusing “some countries” of taking a “selective approach to rules and international laws” or “willfully [interfering] in other countries’ internal affairs and matters.” He asked the audience: “Who is disrupting peace in the region?” We would have been inclined to name China as the most likely culprit but suspect he had the United States in mind.

Implications for ASEAN

At this year’s 36th Asia-Pacific Roundtable in Kuala Lumpur in August, major power confrontation and its implications for the Asia-Pacific region (Indo-Pacific being a less-favored term in Southeast Asia at least) was a central feature in almost all discussions. There was spirited debate between US and Chinese interlocutors (one example is summarized here), with Chinese lamenting the deterioration in bilateral relations while failing to recognize (or at least acknowledge) China’s role in this downturn. Southeast Asian participants were more concerned on the impact major power tensions could have on the already-fragile state of ASEAN unity.

These concerns were best summed up by Malaysian Prime Minister Yab Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim in his Roundtable keynote address. “The intensifying major power rivalry between China and the United States is testing, and straining, the fabric of the region’s longstanding architecture and norms.” After lamenting “the emergence of new mini-lateral groupings across the board, which despite its window dressing, could be cast as exclusive and exclusionary in nature,” Anwar concluded that “It would be a great loss for the entire region if this unfettered rivalry affects all that have been painstakingly achieved by existing and consequential ASEAN-led multilateral mechanisms.”

True, but as other conference discussions highlighted and Anwar himself acknowledged, “continued post-coup violence and instability in Myanmar, remains one of ASEAN’s biggest strategic and humanitarian challenges.” While one could point a finger at Beijing and Moscow for propping up the junta—Anwar didn’t—he did note that a “failure to act [by ASEAN] would be tantamount to a dereliction of collective responsibility.”

Anwar avoided the subject of Ukraine in his prepared remarks. When asked about Kuala Lumpur’s stance on the Russia-Ukraine War in the Q&A session, however, he noted that though war stands in violation of international law, “Russia’s concerns behind the attack” must be taken into consideration.

ASEAN participants were also bound and determined to avoid making what Anwar described as a “binary choice” between the United States and China. Good relations with both were necessary “to promote a stronger rules-and-norms-based order.” Sending a message to both Washington and Beijing, Anwar stressed that “This order is not based on might, or the tendency to ignore the very rules and norms one preaches about when it is inconvenient. That is unconducive and hypocritical.” However, Washington would have little trouble agreeing with him when he argued that “it must be an order based on fairness, respect and understanding, compassion, and international law.”

ASEAN participants had little trouble making a binary choice when it came to the South China Sea, however. Anwar noted that “the continued militarization of the maritime region coupled with the use of grey zone tactics to reinforce claims and stymy the lawful exploitation of resources is neither peaceful nor constructive.” The Philippine and Vietnamese presentations, in particular, pointed a finger directly at Beijing for changing the status quo in these contested waters. And all this was before China further infuriated its neighbors with a new national map reaffirming it’s now 10-dash line claim (the tenth being to the east of Taiwan ). For a summary of all Roundtable discussions, see ISIS-Malaysia’s conference report.

Busy, Busy, Busy

While, as argued earlier, NATO as an organization may not have a direct role to play in the Indo-Pacific, NATO is a model of cooperation and coordination among security partners, and the growing complexity of regional security relationships in the Indo-Pacific will soon demand some rationalization. There is just too much going on for security bureaucracies to just keep piling on meetings, initiatives, and mechanisms.

For example:

After mounting complaints from Australian analysts and UK legislators, the US appears ready to modify International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) that pose significant obstacles to the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) security partnership. While this has immediate implications for the submarine deal that dominates perceptions of AUKUS, it will have longer term, and likely more significant, payoffs in Pillar 2 of the agreement, which concerns new technologies. There are several working groups focused on these technologies, and that expanding body of work has echoes in other bilateral and multilateral security forums.

The first quadrilateral defense leaders meeting, involving Australia, Japan, the Philippines and the United States occurred on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue. The four officials—Defense Ministers Richard Marles, Hamada Yasukazu, Carlito Galvez, and Lloyd Austin, respectively—“reaffirmed that they share a vision for Free and Open Indo-Pacific and collectively make efforts to ensure the vision continues to thrive.”

This was followed two weeks later by the first meeting of national security advisors from the Japan, the Philippines and the US, in Tokyo, at which “they emphasized the importance of enhancing trilateral cooperation and response capabilities based on the Japan-United States Alliance and Philippines-United States Alliance in order to maintain peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.”

The four governments held joint naval exercises in the South China Sea in August. Originally scheduled to be a trilateral, the Philippines joined as tensions increased following Chinese attempts to prevent Manila from resupplying forces in the region.

Then there was the Camp David Summit between the US, Japan, and South Korea in August, which attempted to take advantage of the political moment in the three countries and pushed for the institutionalization of relations between them. The Camp David Summit is discussed in more depth elsewhere in this issue of Comparative Connections, but for us, the key point here is the progress in multilateralization—and the growing burden that it poses for security bureaucracies as relations thicken among allies and partners. In that summit statement, the three leaders pledged to “hold trilateral meetings between our leaders, foreign ministers, defense ministers, and national security advisors at least annually, complementing existing trilateral meetings between our respective foreign and defense ministries. We will also hold the first trilateral meeting between our finance ministers as well as launch a new commerce and industry ministers track that will meet annually. We will also launch an annual Trilateral Indo-Pacific Dialogue to coordinate implementation of our Indo-Pacific approaches and to continually identify new areas for common action.” They will also discuss ways to coordinate efforts to counter disinformation and launch a trilateral development policy dialogue.

All this is applaudable progress, but we have been there before. Prior to the turn of this century, spurred on by the then-historic Statement on a “new partnership” between Japan and Korea, we were talking about a “virtual alliance” among the US, Japan, and Korea as “both possible and essential for long-term peace and stability in the region.” We wish all three better luck this time around.

Add to the above mix developments in all US alliances, the Quad, relations among allies without the US, the economic dialogues, technology consultations and, well, you get the idea. It is a huge and growing menu of conversations and some form of rationalization is required. NATO isn’t the archetype, but it is a model of organization. Something is needed.

That something won’t emerge in the last trimester of the year but the need for some way to make regional security discussions more efficient will become ever more apparent. Keep an eye out for the inklings of an expanded—viz the tri- and multilateral frameworks—regional security conversation. And expect still greater pushback from China, Russia and like-minded nations as they contemplate its purpose and prospects.